by Ronald Lee and Andrew Mason

[Population Aging to 2030, Day 3, Essay 1 of 3]

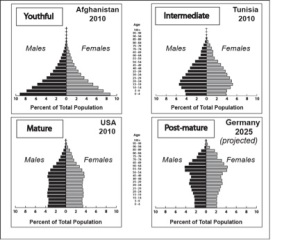

Many countries in Europe and elsewhere are aging rapidly. In part this is occurring because of the enormous strides that have been made in reducing death rates at older ages and in part because of low fertility. Fertility is particularly low in Southern and Eastern Europe where the total fertility rate, the number of births per woman over her reproductive span, is typically around 1.5 or less. This means that the next generation will be twenty five percent smaller than the current generation unless fertility rebounds. This is a recipe for both population decline and an old population, one with more elderly relative to those in the working ages.

Population projections are a powerful tool to look into the future. We can be confident that in Europe the number 65 and older will rise substantially relative to those in the working ages however defined. Demography can tell us only so much, however. The economic effects of changes in population age structure in Europe depend on what people do at each age. This is changing over time and varies considerably across countries depending on health status, values, public policies, standards of living and a variety of other factors.

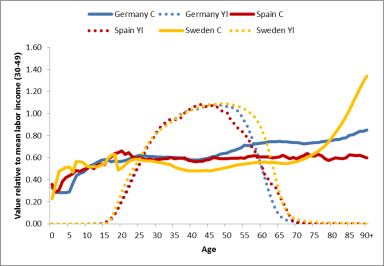

Figure 1. Consumption (C) and labor income (Yl) by age in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Source: National Transfer Accounts

The importance of this can be seen by comparing Sweden, Germany, and Spain. In Spain and Germany labor income declines very rapidly at older ages as compared with Sweden. Swedes in their late 50s and early 60s are producing much more than Germans and Spaniards at those ages. Sweden has a different problem, however, which is very high consumption at older ages, largely due to publicly funded health care casino online and long term care. One could say that Swedes in their 80s are a much greater economic burden, while Germans and Spaniards in their 60s create more strain.

The support ratio, the ratio of effective producers per effective consumer, provides a way of measuring population aging that allows for differences in consumption and best online casino labor income patterns. The support ratio counts people at each age according to what they produce and what they consume as according to the curves in Figure 1.

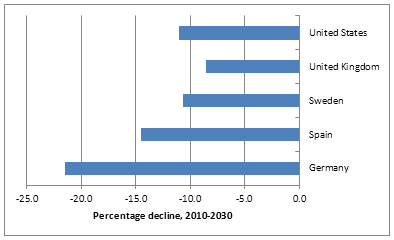

Figure 2. Percentage decline in the support The Carlos Raitzin horoscope cancer is very interesting if you are interested in astrology. ratio, 2010-2030.

By this measure, population aging will have the greatest impact in Germany where the support ratio will decline by over 20 percent between casino 2010 and 2030. Germany has dgfev online casino two factors working against it – low fertility and low labor income among older adults. The decline in the support ratio in Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States is projected to be at about half the rate as in Germany. Spain is roughly in the middle between these two extremes.

The difference between Spain and Germany is online pokies primarily a matter of timing. Germany is aging earlier than Spain because its fertility declined earlier. Both countries will experience a decline in their support ratio by about 25% between 2010 and 2050, about twice as great a decline as in the other three countries.

A final element in thinking about the welfare state and population aging is that countries differ greatly in the mechanisms on which they rely to mobile casino meet the needs of the elderly. In general, countries in Europe rely more on the public sector than in the US or many other countries.

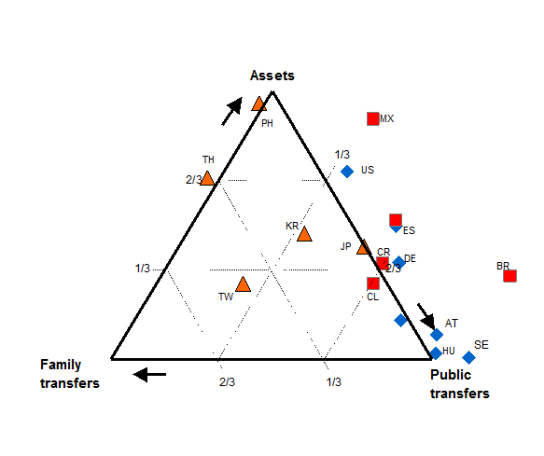

This is clear in Figure 3 which shows the relative contribution of net public transfers, net familial transfers, and asset-based flows to funding the gap between consumption and labor income for those 65 and older.

There is great variation in Europe with Sweden (SE) relying entirely on net public transfer to fund the old-age support system. In Germany (DE), about two-thirds of the support comes from public transfers while in Spain (ES) it is closer to one-half. Population aging will place particular strains on the public old age support system in Sweden.

Figure 3. Old-age support system for selected countries. Public transfers, family transfers, and asset-based flows as a share of the lifecycle deficit for those 65 and older. Source: Ronald Lee and Andrew Mason, lead authors and editors, 2011. Population aging and the generational economy: A global perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Note that all the European countries that are shown in Figure 3 rely very heavily on the public sector to fund net consumption by the elderly. None relies on help from children, and generally they rely very little on assets, unlike the US. Figure 3 also shows that some but not all Asian countries do rely on families to provide old age support. In these countries population aging will also put pressure on adult children of the elderly.

Ronald Lee is Professor of Demography at the University of California, Berkeley, and Chair of the Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging (CEDA). Andrew Mason is Professor, Department of Economics at the University of Hawaii and Senior Fellow at the East West Center. They are Co-Directors of the National Transfer Accounts Project.