[Population Aging to 2030, Day 5, Essay 1 of 2]

International migration is now the dominant driver of population increase in most Western European countries and in the English-speaking world, exceeding natural increase considerably and in some cases approaching the annual total addition to population from births. If current trends persist those populations will become “super diverse” with today’s ‘majority’ population no longer numerically dominant.

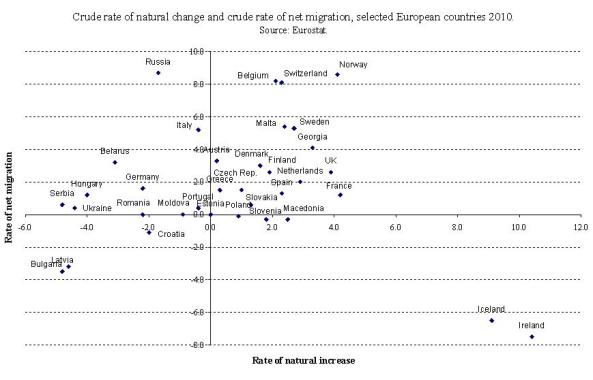

Figure 1. Rate of natural change and rate of net migration, selected European countries, 2010

Birth rates in developed countries are relatively low, equivalent to a family size (total fertility) of no more than two and much lower in some Southern and Eastern European countries. Population change is thus driven primarily by international migration, not natural change (the difference between the number of births and deaths). In some NW European countries population growth has been raised to levels not seen since the early 1970s (as in the US Australia and New Zealand). Rates of natural increase in European countries are nowhere over 0.4 per thousand; many are negative. Net immigration, however, approached 9 per thousand in some in 2010 (Figure 1).

Table 1. Comparison between natural increase and net migration in selected European countries.

In some countries (Table 1) the annual contribution of migrants to population growth (net of emigration) has been almost as great as the annual number of births (Switzerland, Italy), including births to immigrants. But migration can swing from one extreme to another in times of economic crisis.

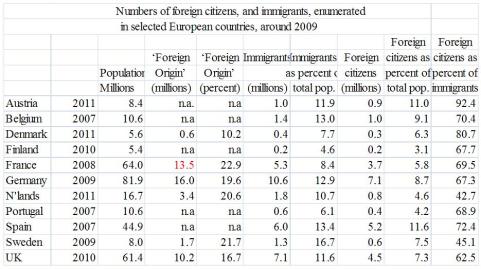

The cumulative effects of immigration since the 1960s have been to raise the proportion of immigrants in national populations from (usually) small single figures to around 10% or more (Table 2). The number of immigrants is often substantially greater than the number of foreigners in any given year. Some countries turn foreigners into citizens almost as fast as they arrive in (e.g. France and the Netherlands) through rapid naturalisation.

Table 2. Number of foreign citizens and immigrants in selected European countries.

Distinctive cultural patterns and needs, residential segregation and socio-economic and other forms of disadvantage have persisted among many immigrant populations. Accordingly, some countries estimate populations of foreign origin beyond the ‘first (immigrant)’ generation. Countries of the English – speaking world ask individuals to specify their ‘ethnic origin’ or ‘ancestry’ in census or survey questions. In continental European countries with population registers, parallel estimates are made through registration data on nationality and birthplace of individuals and of their parents. In the former, the ethnic ascriptions extend potentially over an unlimited number of generations. In the latter, the ‘third generation’ is assumed to have become ‘native’ (i.e. ‘Danish’, ‘Dutch’, etc.) and casino online disappears from statistical view. According to these estimates the population online pokies of ‘foreign origin’ or ‘foreign background’ had increased to about 20% of the national total by 2010.

In the US, the non-European racial diversity represented by the US black population was is not of recent immigrant origin. Usually the major national origin components – Moroccans, Turks, Somalis, etc. are projected separately, and broadly grouped into ‘Western’ or ‘High Human Development Index (HDI)’ (people mostly of European origin) or non-Western (people of non-European origin) from countries of middle or low HDI.

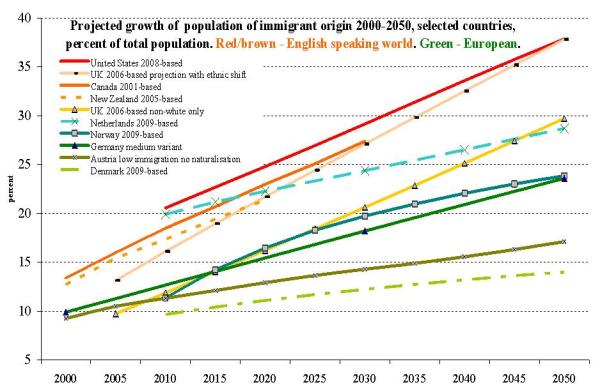

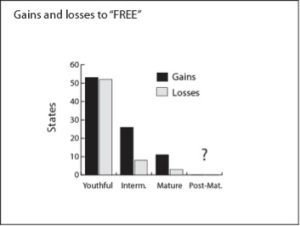

Figure 2 shows an approximately linear increase of the minority groups to between 20% and over 30% of the national population by the end of the projection period (usually 2050 or 2060). The level of net migration is usually assumed to remain constant, given the difficulty of predicting migration. Those for Norway and The Netherlands are exceptions. In the UK, the favoured variant projection by Rees and his colleagues assumes that dgfev online casino return migration will increase pro rata with growing minority numbers, leading to markedly slower projected growth of the minority populations compared with the highest variant from this author. Later projections for Denmark and The Netherlands in the last decade indicate more modest minority growth than earlier ones, following reductions in immigration partly following restrictive policy initiatives.

Figure 2. Projection of immigrant population by region.

The continuation of these trends online casino in low-fertility countries would eventually lead to the numerical eclipse of the former majority population, assuming that the defined groups remain discrete. The latest US projections assume that the US will become the first industrial country to have a ‘majority minority’ population in about 2043, although there the black population Whereas the opposition to Neptune suggests attraction to illicit drugs, it also heralds artistic talents, which are efficient because they are indefinable or even magnetic (Taurus- scorpio love horoscope axis). is not, for the most part, of recent immigrant origin. Excitable and unscientific projections apart, few projections of European populations have extended far enough into the future to reach a similar outcome. One projection for the UK (assuming the continuation of recent migration and fertility levels) indicates that all ethnic minority populations together would exceed the number of ‘White British’ at around 2070.

A comprehensive analysis made on a common methodology for all the EU countries was published by Eurostat in 2010, on four different scenarios. The most conservative of these estimated that 26.5% of the EU population would be of ‘foreign background’ by 2061, the highest model being 34.6%. Among larger countries, the lowest estimate overall was for Bulgaria (7%); the highest for Belgium, Germany, Spain and Austria, all around 50%.

However, 60 years is a long time in demography and these projections can only illustrate the consequences of specified assumptions. Migration can, and does, go down as well as up- notably in Germany, The Netherlands and Spain in the last few years, and recently from Mexico into the United States. Populations of mixed origins are increasing fast and will have a profound effect on the social scene and on concepts of ethic identity and categorisation.

But none of this is graven in stone. Most depends on migration rates. While their high level may seem inexorable, international migration is the most volatile of demographic components, subject to multiple economic and political uncertainties, and at least in theory subject to policy control. The magnitude of the challenges presented by these trends is very great – to society, national identity, domestic and foreign policy.

David Coleman is Professor of Demography in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at Oxford University.

References Cited.

Caldwell, C. (2009). Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. Immigration, Islam and the West. London, Allen Lane.

Coleman, D. A. (2006). “Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: a third demographic transition.” Population and Development Review 32(3): 401 – 446.

Coleman, D. A. (2009). “Divergent patterns in the ethnic transformation of societies.” Population and Development Review 35(3): 449 – 478.

Coleman, D. A. (2010). “Projections of the Ethnic Minority Populations of the UK, 2006 – 2056.”Population and Development Review 36(3): 441 – 486.

Lanzieri, G. (2011). Fewer, older and multicultural? Projections of the EU populations by foreign/national background Luxemburg, Eurostat. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-RA-11-019/EN/KS-RA-11-019-EN.PDF

Steinmann, G. and M. Jaeger (2000). “Immigration and Integration: Non-linear Dynamics of Minorities.”Journal of Mathematical Population Studies 9(1): 65 – 82.

United Nations (2000). Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?New York, United Nations.

Wohland, Pia , Phil Rees, Paul Norman, Peter Boden and Martyna Jasinska (2010) Ethnic population projections for the UK and local areas, 2001-2051. Working Paper 10/02, School of Geography, University of Leeds. http://www.geog.leeds.ac.uk/research/wpapers